God bless North Dakota. This state has a bleak and somewhat forlorn majesty and beauty of its own, although sometimes you have to look below the surface to find it. But trees, due to the lack thereof, are not this state’s crowning glory, and the trees that are here have little to boast about compared to their glorious cousins that inhabit the lofty mountains and verdant valleys of the western regions of the Pacific Northwest.

In all reality, it seems that North Dakota has more bent, tilting, and clanking farm windmills, more lifeless, and rusting century-old threshing machines sleeping silently out in farmers’ fields along with countless grain silos standing as sentinels over railroad tracks, as well as abandoned and derelict barns and houses than it has trees trees. So when I discovered that the Minot area of north central North Dakota, just below the Canadian border, where I am visiting family, had an experimental forest and an arboretum, this tree geek arborist had to check it out.

Forest and arboretum, I mulled in my mind. Naturally this Oregon native conjured up park-like images in his fertile imagination.

To get to this forest, we had to drive for miles through endless, virtually treeless fields of wheat, soybean, rapeseed, flaxseed and sunflower along with pastures speckled with sheep and cattle sprawling across the pancake flat landscape as far as the eye could see, while traveling at 70 miles per hour on a straight, virtually carless highways that reached to the horizon. The only trees, for the most part, were the phalanx like windbreaks planted around the occasional lone farmhouse to shield it from the howling winds and the searing summer heat. The landscape also boasted, if you can call it that, a few thirsty trees growing along the fringes of a few creeks and watersheds here and there, and along old fence lines where birds have perched and deposited tree seeds. After all of this, we finally reached the Denbigh Experimental Forest.

As a native Pacific Northwesterner, who has spent a lifetime tramping up and down in our coastal and Cascade Mountains, I wasn’t sure what to expect in North Dakota where there are probably more honking Canada geese grazing in wheat fields than trees.

My initial response was: “This is it??? This is what they call a forest?”

We exited our car and hit a hiking trail. Immediately the forest floor was littered with the carcasses of countless trees that had succumbed to the pitiless ravages of the fierce climate and harsh growing conditions that this region offers its flora. Many more trees were standing lifeless or were half dead. The fierce plains winds had knocked countless trees down. Many more were leaning precariously against their neighbors for support, creaking eerily in the wind as they rubbed themselves raw against one another. After nearly a hundred years, few trees were more than 60 feet tall and a foot or two in diameter. In western Oregon from where I come, trees of this age would be more than twice as tall and thick. Needless to say, I was not impressed, to say the least.

But I had come this far to see said forest, so I was determined to discover something unique and wonderful about it. I refused to be put off by its shabby and pitiful outward appearance.

And sure enough, I was in for a pleasant surprise. You’d think by now, at my age, I’d have learned not to judge a book by its cover.

Yes, on the surface, what I found, in all honesty, was the about the saddest forest I had ever seen in my life of traveling in some 22 countries on four continents. Yet, it was still a forest, and in my book, this is something still to be cherished and even respected. Again, it might take some creative searching, but I was hopefully predetermined to find something special here.

The Denbigh Experimental Forest was established by the USDA Forest Service in 1931 “to determine which trees could survive and thrive in the harsh northern Great Plains climate,” says the brochure at the forest’s parking lot kiosk. Sadly, in its past life, this 636 acre site had been “extensively over-plowed and overgrazed during the early part of the 20th century, leaving wind-blown sand dunes”, according to Wikipedia. As a result of man’s mismanagement, it had become a wind-blown, eroded and forsaken dust bowl.

Visionary men, under the leadership President Franklin Roosevelt, had established this experimental forest with the more modest goals of determining which types of shelterbelt trees would grow well in the northern Great Plains, which seed sources within species are best adapted for the region, and which methods of tree establishment are most effective for shelterbelts. As a result, some 40 species of trees were planted there of which 30 have survived (ibid). This is in spite of the mere 18 inches of rainfall the area receives per year, the 1,200 foot elevation, the short growing season, the harsh winters that pile multiple feet of snow on the area during the interminably long winters, and temperatures that can plunge to negative 60 degrees below zero, not to mention the frequent winds that blast across the open prairie strong enough to blow cars off the roads. For example, it’s now early April and the snow cover has just finally melted, but plenty of snow still remains in sun-sheltered areas behind buildings and hills, in gulches, and in massive piles in the back corners of shopping center parking lots. The fields of grass are still brown from months of smothering snow cover, and only a few blades are now just beginning to green up. Though it is officially spring, there is not a blooming flower to be found anywhere in town (except for the plastic flowers that decorate the graves of Minot’s local cemetary), in the fields or forests. Plant life is only now—in early April—beginning to arouse after months of hibernation under blankets of snow. The trees are still leafless, although the aspens are beginning to break bud.

So, when all of these environmental and climatological factors are taken into account, this ostensibly poor excuse for a forest, in reality, is quite amazing considering all that it has endured these past 91 years. The fact that any of it has survived in and of itself seems like a bit of a miracle.

What’s more, the Denbigh forest illustrates the earth’s ability to heal itself (with a little help from its human counterparts) after having been ravaged by man’s past careless and indifferent mismanagement.

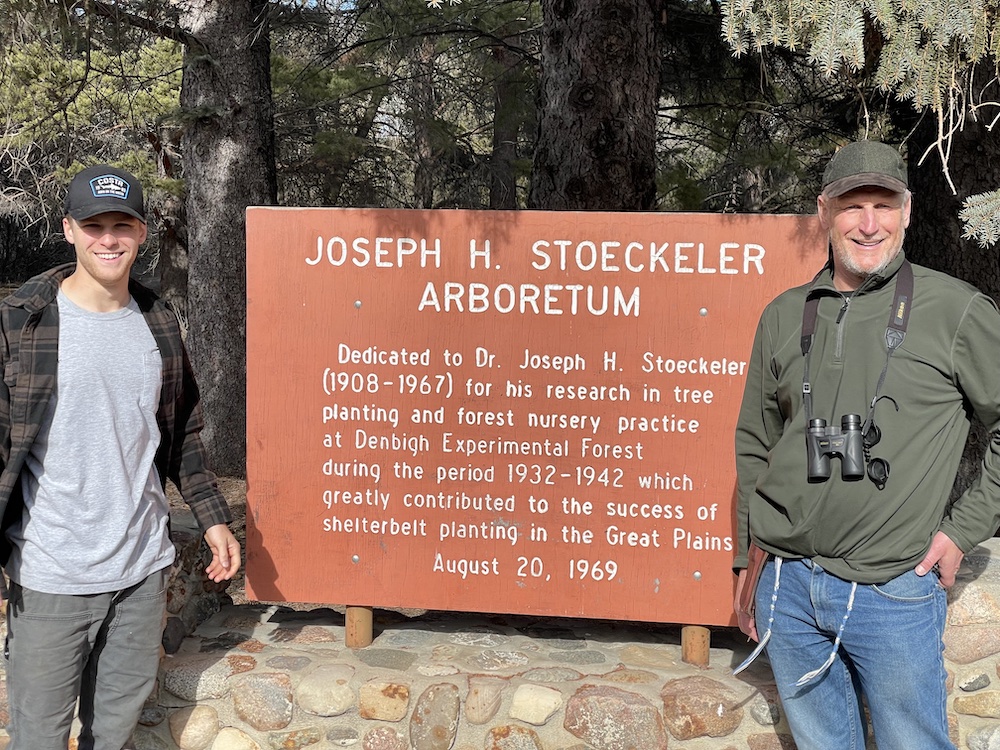

Please enjoy the pictures I took of the Denbigh Experimental Forest and the Joseph H. Stoeckeler Arboretum contained therein.

And now something for the tree geeks in the crowd—

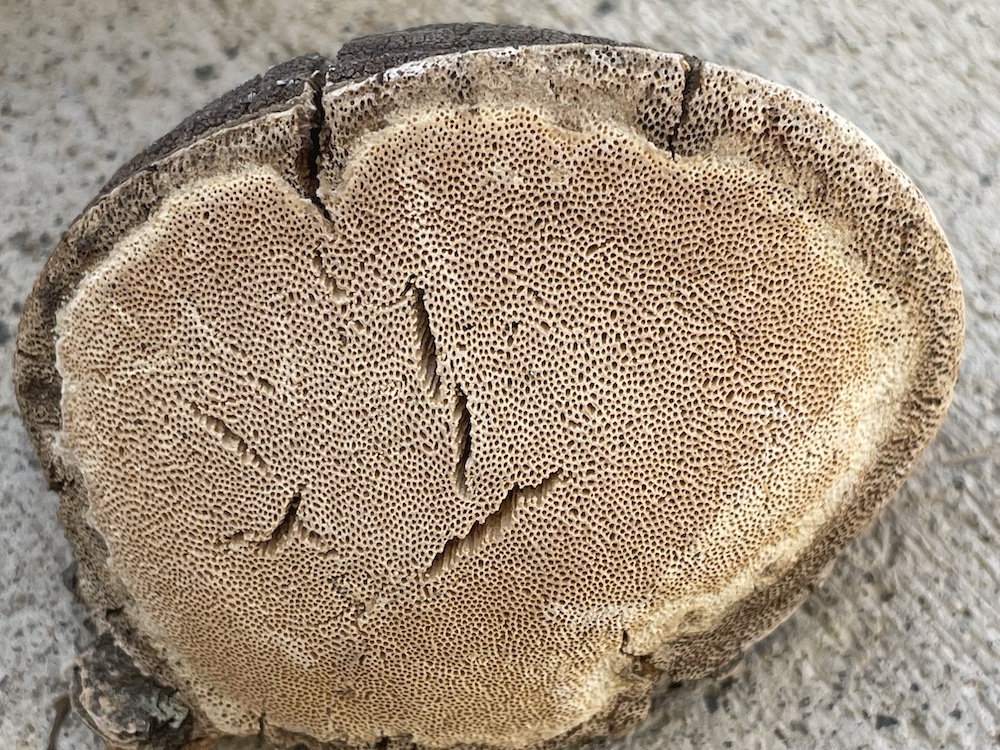

Here are some photos of polypores (aka conks, shelf or bracket fungi) that are the fruiting bodies of various basidiomycetes (mushroom type fungi) that I found growing in in this North Dakota forest. I found both conks that attack and feed on living trees and that feed on dead trees. Some conks feed on both living and dead trees. I don’t know the specific varieties, since they are different than the ones I have found in my local Oregon forests, but here are some fun pictures anyway.