The Mediterranean oak borer (MOB) is the latest invasive insect pest to afflict NW Oregon, and this time it is the iconic native Oregon white oak—the crown jewel of this areas deciduous trees. Many of these oak trees are six or more feet in diameter and can be more than 200 years old, yet, believe it or not, the MOB can cause the demise of these majestic giants in only a couple of years. In this video, you will learn the latest up to date intel about the MOB from the state’s top experts, and what you can possibly do to save your oak tree.

Category Archives: Tree Pests

Treating Ash Trees Against Emerald Ash Borer in Portland

The Emerald Ash Borer Beetle—How to Save Your Ash Tree

The emerald ash borer beetle is now in the Portland, Oregon, area and is spreading rapidly. In a few years, nearly all the ash trees will be dead including yours, unless you take preventative measures. In this video, Nathan explains what you can do to save your ash tree. In most cases, an ash tree can be treated for 20 to 30 years for the cost of removing it. Check out this video and learn all about it. For a deep dive into this subject, check out our longer video at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rBTADVg5KpE. Cheers!

Emerald Ash Borer Beetle Hits NW Oregon–Problem/Solution Explained

In this video, Nathan goes into detail explaining everything about the emerald ash borer beetle (or EAB) that has recently hit NW Oregon (in the Portland area) and is rapidly spreading. This destructive, invasive pests kills ALL ash trees that it infests within several years. Nathan discusses the pros and cons of saving your ash tree, treatment options, costs and how to identify signs and symptoms of the beetle on your tree.

- For more info on the EAB, go to https://www.aphis.usda.gov/aphis/newsroom/stakeholder-info/stakeholder-messages/plant-health-news/eab-or

- https://www.oregon.gov/oda/programs/IPPM/SurveyTreatment/Pages/EmeraldAshBorer.aspx

- https://static1.squarespace.com/static/58740d57579fb3b4fa5ce66f/t/60772a17647ad466155f74a7/1618422303582/March+2021_EAB.pdf

- https://www.oregon.gov/oda/programs/IPPM/Documents/EmeraldAshBorer.pdf https://catalog.extension.oregonstate.edu/sites/catalog/files/project/pdf/em9160.pdf

- https://oregoninvasiveshotline.org

- https://extension.oregonstate.edu/forests/cutting-selling/what-do-about-emerald-ash-borer-recommendations-tree-protection-eab

- http://www.emeraldashborer.info

- https://www.invasivespeciesinfo.gov/terrestrial/invertebrates/emerald-ash-borer

- https://www.aphis.usda.gov/aphis/ourfocus/planthealth/plant-pest-and-disease-programs/pests-and-diseases/emerald-ash-borer

- https://www.aphis.usda.gov/aphis/resources/pests-diseases/hungry-pests/the-threat/emerald-ash-borer/emerald-ash-borer-beetle

- https://www.aphis.usda.gov/plant_health/plant_pest_info/emerald_ash_b/downloads/What-is-the-EmeraldAshBorer.pdf

- https://www.arborday.org/trees/health/pests/emerald-ash-borer.cfm

The Emerald Ash Borer Tree Killer—What it is and what to do about it

There’s a new tree pest in town called the emerald ash borer (or EAB) and it wants to kill all the ash trees in this area.

The Emerald Ash Border (or EAB) was discovered in the summer of 2022 in hundreds of trees in the Portland Metra area and is spreading rapidly throughout the region.

According to the Oregon Department of Agriculture, the EAB “is a highly destructive invasive forest pest” that has killed over 100 million ash trees so far in the US. It moves quickly, and can cause nearly complete mortality of ash trees within about several years after detection. There are no effective means of eradicating the EAB once the insect is established in an area. Once a tree canopy has been thinned or been reduced by 20 to 30 percent or more by EAB feeding activity, it is too late to save the tree. It will die.

Good News Tree Service, Inc. can save your ash tree from the EAB beetle before it’s too late. CALL US TODAY FOR MORE INFO!

Frequently Asked Questions About the EAB

What trees species does the Emerald Ash Borer attack?

The EAB attacks all varieties of ash or Fraxinus trees regardless of variety, size, age or the health status of the tree. It also attacks the white fringetree (Chionanthus virginicus) and cultivated olive trees (Olea europaea).

How quickly does EAB spread?

The beetle can fly several miles (sometimes up to 15 miles) from one infested tree to one that is not. However, the most likely means by which the EAB spreads is thought to be by hitchhiking on vehicles and by translocated firewood. That’s why the EAB is more likely to spread to trees in areas along major freeways and highways, which opens up the entire Willamette Valley to the EAB.

How quickly will the EAB kill my tree?

An ash tree usually dies within four to six years after initial infestation. For the first couple of years of EAB infestation, it may be impossible to detect EAB activity in a tree, which is why trees worth saving need to be treated earlier rather than later.

What are the signs that my tree has EAB?There are several including:

- Thinning of a tree’s crown.

- Branch dieback.

- Woodpecker activity.

- One-eighth inch sized capital “D” shaped holes in the bark of the tree.

- Splitting bark.

Progression of EAB symptoms in a tree, which may occur a couple of years after the tree has already been infested include:

- Year one: no crown thinning.

- Year two: moderate crown thinning.

- Year three to four: heavy crown thinning and death.

What are my options when it comes to EAB?

- Do nothing. Then wait for your tree to die as you unwittingly facilitate the spread of the EAB to your neighbors’ ash trees.

- Remove the tree. If your ash tree is small (smaller than six inches in diameter), we recommend removing it and replacing with another species of tree. The cost to remove an ash tree and its stump can be $1,500 or more. This does not factor in the diminished value to your property that the removal of a mature tree will cause. In Portland, for example, the assessed value of mature ash tree is $3,12013. Plus, this not cover the cost to replace the tree, which is often a requirement in many municipalities.

- Treatment. Considering treating high-value ash trees with an insecticide, which is a proven way of protecting your tree. Keep in mind that this will cost hundreds of dollars and must be repeated every few years, thus requiring a long-term commitment.

Is there anything I can do to protect my ash tree?

Other than treating your tree with a systemic insecticide, the answer is no.

How effective are treatments?

If an ash tree is treated in time, usually before 20 to 30 percent defoliation occurs, the survival rate is about 99 percent. After that level of defoliation occurs, will die the tree thus becomes a standing hazard requiring removal.

What is the cost to treat my ash tree for EAB?

The cost to treat an average sized ash tree (20 inch diameter at breast height) is around $300 to $400 (or less for quantity discounts). Generally one can treat an ash tree for 20 to 30 years for the same cost as removing it and replacing it with another tree. Often local municipalities require that you replace your tree especially if it is a street tree, which adds to the overall cost of removing a tree.

How often do I need to treat my tree?

An ash tree will need to be treated only once very two to three years, and will need to be treated for the life of the tree.

How are the treatments applied and are they environmentally safe?

Yes! Absolutely. The systemic insecticide we use is injected directly into the tree’s vascular system (like and IV), so it all goes into the tree, thus there is no residue present to harm pets or people. The product we use also doesn’t harm bees or other pollinators.

More Info About EAB

Oregon State University Extension Service— general info: https://extension.oregonstate.edu/forests/cutting-selling/what-do-about-emerald-ash-borer-recommendations-tree-protection-eab

Oregon State University—EAB identification guide: https://catalog.extension.oregonstate.edu/sites/catalog/files/project/pdf/em9160.pdf

OSU Extention Service–general info and more links: https://extension.oregonstate.edu/announcements/emerald-ash-borer-quarantine-adopted-washington-county-effective-dec-20-2022-may-16

OSU Extention Service:

https://extension.oregonstate.edu/forests/cutting-selling/what-do-about-emerald-ash-borer-recommendations-tree-protection-eab

Footnotes

1–EAB confirmed in Oregon: https://www.aphis.usda.gov/aphis/newsroom/stakeholder-info/stakeholder-messages/plant-health-news/eab-or

2–Oregon Department of Agriculture: https://www.oregon.gov/oda/programs/IPPM/Documents/EmeraldAshBorer.pdf

3– Oregon Department of Forestry: https://static1.squarespace.com/static/58740d57579fb3b4fa5ce66f/t/60772a17647ad466155f74a7/1618422303582/March+2021_EAB.pdf

Save Your Ash Trees NOW from the New Killer Pest in Town!

Stay tuned for more info on how to protect your ash trees from this deadly pest that recently hit the Portland area and is spreading throughout the region. Your ash trees will likely die within four to six years if not treated NOW!

Soon we will be posting answers to frequently asked questions about this deadly killer including:

- How to know if your tree is an ash tree.

- How to identify the symptoms of emerald ash borer infestation (or EAB).

- What the most effective and least expensive treatments are.

- When to treat your ash tree.

- What will happen if you do not treat your ash tree.

North Dakota’s Pitiful and Yet Amazing Forest

God bless North Dakota. This state has a bleak and somewhat forlorn majesty and beauty of its own, although sometimes you have to look below the surface to find it. But trees, due to the lack thereof, are not this state’s crowning glory, and the trees that are here have little to boast about compared to their glorious cousins that inhabit the lofty mountains and verdant valleys of the western regions of the Pacific Northwest.

In all reality, it seems that North Dakota has more bent, tilting, and clanking farm windmills, more lifeless, and rusting century-old threshing machines sleeping silently out in farmers’ fields along with countless grain silos standing as sentinels over railroad tracks, as well as abandoned and derelict barns and houses than it has trees trees. So when I discovered that the Minot area of north central North Dakota, just below the Canadian border, where I am visiting family, had an experimental forest and an arboretum, this tree geek arborist had to check it out.

Forest and arboretum, I mulled in my mind. Naturally this Oregon native conjured up park-like images in his fertile imagination.

To get to this forest, we had to drive for miles through endless, virtually treeless fields of wheat, soybean, rapeseed, flaxseed and sunflower along with pastures speckled with sheep and cattle sprawling across the pancake flat landscape as far as the eye could see, while traveling at 70 miles per hour on a straight, virtually carless highways that reached to the horizon. The only trees, for the most part, were the phalanx like windbreaks planted around the occasional lone farmhouse to shield it from the howling winds and the searing summer heat. The landscape also boasted, if you can call it that, a few thirsty trees growing along the fringes of a few creeks and watersheds here and there, and along old fence lines where birds have perched and deposited tree seeds. After all of this, we finally reached the Denbigh Experimental Forest.

As a native Pacific Northwesterner, who has spent a lifetime tramping up and down in our coastal and Cascade Mountains, I wasn’t sure what to expect in North Dakota where there are probably more honking Canada geese grazing in wheat fields than trees.

My initial response was: “This is it??? This is what they call a forest?”

We exited our car and hit a hiking trail. Immediately the forest floor was littered with the carcasses of countless trees that had succumbed to the pitiless ravages of the fierce climate and harsh growing conditions that this region offers its flora. Many more trees were standing lifeless or were half dead. The fierce plains winds had knocked countless trees down. Many more were leaning precariously against their neighbors for support, creaking eerily in the wind as they rubbed themselves raw against one another. After nearly a hundred years, few trees were more than 60 feet tall and a foot or two in diameter. In western Oregon from where I come, trees of this age would be more than twice as tall and thick. Needless to say, I was not impressed, to say the least.

But I had come this far to see said forest, so I was determined to discover something unique and wonderful about it. I refused to be put off by its shabby and pitiful outward appearance.

And sure enough, I was in for a pleasant surprise. You’d think by now, at my age, I’d have learned not to judge a book by its cover.

Yes, on the surface, what I found, in all honesty, was the about the saddest forest I had ever seen in my life of traveling in some 22 countries on four continents. Yet, it was still a forest, and in my book, this is something still to be cherished and even respected. Again, it might take some creative searching, but I was hopefully predetermined to find something special here.

The Denbigh Experimental Forest was established by the USDA Forest Service in 1931 “to determine which trees could survive and thrive in the harsh northern Great Plains climate,” says the brochure at the forest’s parking lot kiosk. Sadly, in its past life, this 636 acre site had been “extensively over-plowed and overgrazed during the early part of the 20th century, leaving wind-blown sand dunes”, according to Wikipedia. As a result of man’s mismanagement, it had become a wind-blown, eroded and forsaken dust bowl.

Continue readingThere’s a New Plant Villain in Town Called the Azalea and Rhododendron Lace Bug

Are you wondering why some of your rhododendrons and azaleas are taking on a shabby whitish-yellow look as if some graffiti artist snuck into your yard and airbrushed them with paint while you were asleep? Or maybe you think they sport a pale coat because you neglected to fertilize them, or maybe…. Well, it’s none of the above. These ornamental shrubs look this way because there’s a new villain in town that’s literally sucking the life out of your plants, and it’s called the lace bug, and it’s not going away. Let’s introduce you to your new, not so friendly neighbor is and what you can do about it this pesky little insect.

What is azalea and rhododendron lace bug?

The lace bug is a tiny insect that uses its piercing-sucking mouthparts to suck the sugars of the green chlorophyll out of the leaves of broadleafed evergreen trees and plants. This action causes significant damage to the leaves by reducing their ability to produce food for the plant. If the lace bug infestations is severe, this can weaken a plant thus stressing it to the point where it becomes more susceptible to other pests and diseases. We will discuss what you can do to protect your plants from this bothersome pest.

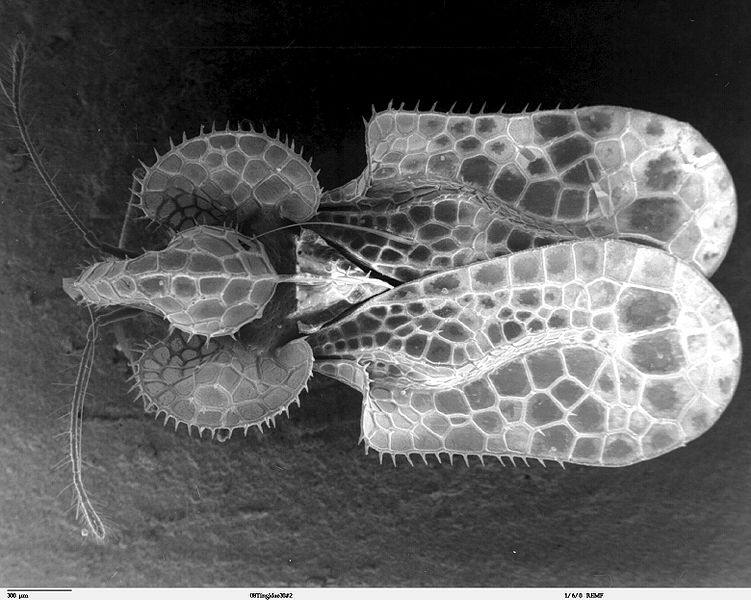

At one-tenth to three-eighths of inch long, the adult lace bugs are whitish-tan in color with a thorax (body)and transparent wings sculptured with an intricate pattern of veins that resembles lace. There are approximately 140 varieties of lace bugs in North America. The one that feeds primarily on azaleas has smoky brown markings on its wings, which distinguishes it from the pale whitish-tan rhododendron (or rhody) lace bug. The juvenile lace bugs or nymphs, which emerge in the spring, are colorless to black in color, pointed on both ends and may have spines depending upon their age.

What is the life cycle of the lace bug?

Lace bugs are a hardy creature that can overwinter under bark scales in trees. They also lay eggs along the mid-ribs on the underside of leaves that resemble crusty brown patches. Depending on the temperatures, they can emerge anytime from mid-April to early June. The warmer the spring, the earlier they will hatch.

They primarily spend their lives feeding on the underside of leaves.

What plants do lace bugs attack?

To this date, here is a list of plants that lace bugs are finding delicious. This list seems to be growing.

Continue readingWhy Do Mature Trees Suddenly Die?

Why did my mature conifer (cone bearing) or deciduous (trees that lose their leaves in the fall) trees suddenly die? Arborists often get asked this question by grieving tree owners. This question deserves a serious answer, since an unbreakable bond exists between humans and trees, and when that link is unexpectedly broken, there are negative consequences for humans and the environment. This is because trees have such a large impact on our lives and often impact all types of human activities. Moreover, whether we are consciously aware of it or not, our lives are intertwined with trees, and even depend upon them for our survival, and when we lose them there are economic, social and cultural, emotional and environmental consequences. If we understand why trees die, maybe we can proactively help to keep them alive.

So why do trees die? And if we understand the reasons why they die, perhaps through wise and knowledgeable actions on our part, we can help to keep the trees in our lives alive longer. After all, as caretakers of this planet, it is our responsibility to care for the small piece of real estate over which we’ve been given stewardship including the trees on it. Face it, the simple fact is that without trees, all animal and human life will die!

With these things in mind, many years ago, as a tree care professional—in the industry, we’re called arborists—I felt that I was taking out too many trees that I knew were savable. Therefore, I rolled up my sleeves and got the necessary education, credentials, licenses and then purchased the equipment to begin providing plant health care services in my tree care company. Since then, I have saved hundreds, if not thousands of trees from their demise. This has been a rewarding activity for me on many levels.

But along the way, I have found that there is a belief among many of my clients that all trees have a life span and eventually grow old and die. For many people, this seems to explain why their yard tree suddenly died. Yet, in my decades as an arborist, I have found this belief usually to be unfounded. Since there are so many variable factors that contribute to tree mortality, it’s often not easy to determine why a tree has died without conducting extensive and costly forensics. Suffice it to say, many of the factors listed below combine to stress a tree, and if the tree doesn’t possess a sufficient reserve of stored energy to combat its stressors, it will eventually succumb to these stressors. Almost everything that a tree does is in slow motion. It grows slowly, its metabolic processes occur slowly and it usually dies slowly as well. On occasion, a tree dies quickly (in a few weeks or months), but this is rare. Like the rest of us, a tree has a strong survival instinct and wants to live. In fact, it contains many built in mechanisms to insure that it survives come what may. So to say that a tree has a certain life span and then it just dies is a misnomer. True, some trees are able to live for hundreds, even thousands of years, while other trees are relatively short lived, by comparison. But under the right conditions and with the right care, nearly any tree you plant in your yard can outlive you and probably your grandchildren too.

The Reasons Trees Die

So now let’s discuss why trees. The following is a list of some of the more common reasons of tree mortality.

Drought. Like humans and all animal life, plants need water to survive. No water, no life. Trees suck up an immense amount of water out of the soil on a continual basis, especially during the growing season. If they don’t obtain the water they need, the go into stress mode. If this continues long enough, they will slowly die of thirst.

Continue readingDid someone shoot your ornamental flowering fruit trees with a shotgun?

Identifying and Treating Flowering Plum, Cherry and Apple Trees Leaf Blights

In the spring and early summer in the Portland and Wilsonville region, do the leaves on your fruiting or ornamental plum, cherry (Prunus spp.) or flowering crab apple (Malus spp.) trees look as if someone was using them for target practice with a shotgun? Are the leaves all peppered with a gazillion small holes?

Not to worry, your miscreant neighbor doesn’t have a vendetta against either you or your trees. However, an airborne fungal pathogen called coryneum blight or “shothole fungus” is most likely the culprit for the cherry and plum trees. For crabapple trees, a different fungus called apple scab with similar symptoms as coryneum blight is likely the guilty party.

On the flowering cherry and plum trees, “shothole fungus” (Thyrostroma carpophilum formerly called Wilsonomyces carpophilus) overwinters in dormant infected leaf buds, blossom buds and Continue reading